Astronomical telescopes are of two basic designs: refractors, which use lenses to gather and focus light, and reflectors, which do the same thing, but with mirrors. Making satisfactory mirrors was difficult, but reflectors’ larger size, better images, and suitability for photography brought the age of large refractors to an abrupt close at the end of the 19th century. The 36-inch Crossley Reflector played a pivotal part in that game-changing swerve.

Astronomical telescopes are of two basic designs: refractors, which use lenses to gather and focus light, and reflectors, which do the same thing, but with mirrors. Making satisfactory mirrors was difficult, but reflectors’ larger size, better images, and suitability for photography brought the age of large refractors to an abrupt close at the end of the 19th century. The 36-inch Crossley Reflector played a pivotal part in that game-changing swerve.

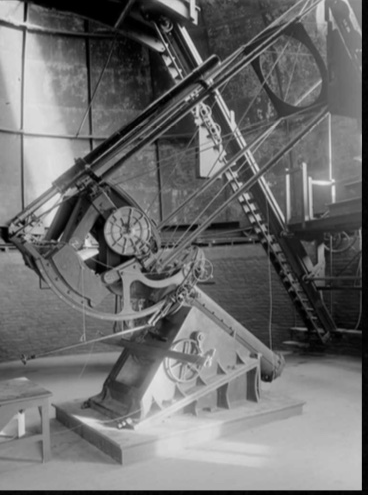

In 1895 Edward Crossley, a wealthy Yorkshire amateur, donated his 36-inch reflector to Lick Observatory, but it proved difficult to operate. In 1898, in the capable hands of Lick’s young second director, James E. Keeler (1857-1900), important discoveries began to flow from the Crossley telescope.

In 1895 Edward Crossley, a wealthy Yorkshire amateur, donated his 36-inch reflector to Lick Observatory, but it proved difficult to operate. In 1898, in the capable hands of Lick’s young second director, James E. Keeler (1857-1900), important discoveries began to flow from the Crossley telescope.

Among these was Keeler’s recognition that the hundreds of “spiral nebulae” found in his long-exposure photographs were a fundamentally important class of celestial object. We now know that Keeler’s “nebulae” are among the billions of galaxies that populate the universe, and his work is regarded as a major early contribution to modern cosmology.

Keeler convincingly demonstrated the utility of reflectors and the power of celestial photography. Though he died tragically young in 1900, at the age of 42, the Crossley went on to have an exceptionally long and productive career. Soon after Keeler’s death, the telescope was completely rebuilt.